Targeting styles with media queries

By Mike Sierra

Summary

Media queries offer an easy way for the client browser to assign different mobile, tablet, and desktop interfaces.

CSS media queries offers an easy way to target custom interfaces to more than one kind of device. This tutorial shows how to use them to optimize a site for mobile handsets and tablet devices in addition to desktop browsers.

The media query feature provides a way for a client browser to respond based on inherent characteristics of the device on which it runs. This avoids the need for server-side device detection, which responds to the User-Agent header the browser transmits with each HTTP request, but which itself only hints at the handset’s size or capabilities.

Assigning alternative interfaces

Media queries extend an older CSS specification known as media types, which assigned browsers to high-level categories such as screen and handheld, or print to re-style a web page’s printed output. The original set of mobile browsers were assigned with the handheld type. Their much lower capabilities meant they could safely be presented with far more simplified content than screen content. However, the introduction of higher-capability touch-based browsers led to a problem: their larger screens and flexible zoom controls allowed them to display complex page layouts intended for desktop browsers. To allow access to richer content, these browsers had to be categorized, somewhat confusingly, as the screen media type.

Unlike media types, media queries offer more details about the device. Most modern touch-based browsers have 320 pixel-wide screens, which can be expressed with the following media query:

screen and (max-width: 320px)

Media queries are enclosed in parentheses and associated with media types with the and keyword. Otherwise, commas separate more than one set of criteria. This specifies a media type and query combination along with an additional media type.

screen and (max-width: 320px), handheld

There are three ways to specify media queries:

- As part of link tags within the HTML’s head region. This example targets CSS to tablet and touch browsers, along with lower-end legacy mobile browsers:

<link media="screen"

href="/path/to/global.css" type="text/css" rel="stylesheet"/>

<link media="only screen and (max-width: 320px)"

href="/path/to/touch.css" type="text/css" rel="stylesheet"/>

<link media="only screen and (max-width: 1024px)"

href="/path/to/tablet.css" type="text/css" rel="stylesheet"/>

<link media="handheld"

href="/path/to/mobile.css" type="text/css" rel="stylesheet"/>

- As part of @import rules within CSS files or style regions:

@import url("/path/to/touch.css") only screen and (max-width: 320px);

- As part of @media rules that define regions of custom style sheets within a single CSS file or style region. This example styles a sidebar element, but hides it from the mobile interface:

aside.sidebar { float: right; }

@media only screen and (max-width: 320px) {

aside.sidebar { display: none }

}

The first two approaches allow you to conditionally load entire CSS files, while the third may be easier to maintain core style sheets alongside custom variations.

Note: In the examples above, the only keyword filters out the shrinking number of legacy browsers that interpret media types ('screen) but not the accompanying media query syntax. A similar not keyword reverses what a media query matches. This example detects optional features, excluding any browser that is sensitive to orientation:

not all and (orientation)

Example: Adaptive screen layout

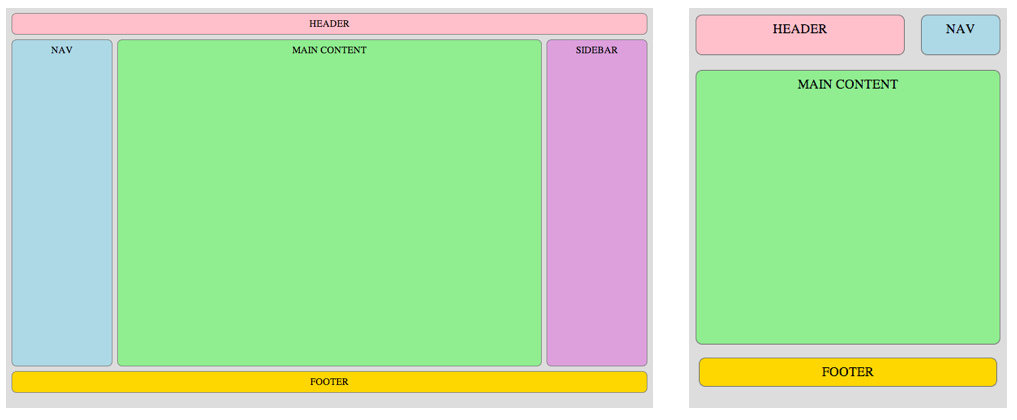

The best thing you can do with media queries is design alternate screen layouts. This skeletal layout relies on a single set of HTML tags:

<body>

<section class="page">

<header> HEADER </header>

<section class="content">

<nav> NAV </nav>

<article> MAIN CONTENT </article>

<aside> SIDEBAR </aside>

</section>

<footer> FOOTER </footer>

</section>

</body>

Media queries allow you to specify much different layouts depending on available screen width:

The core set of style sheets specifies a desktop-facing layout using flexible box CSS properties:

body {

background : #ddd;

text-align : center;

}

section.page {

display : flex; /* use flexbox */

flex-wrap : wrap;

flex-direction : column; /* nested items stack vertically */

justify-content : space-between;

align-items : stretch;

align-content : stretch;

min-height : 40em;

}

section.content {

display : flex;

flex : 1; /* item expands to fill space within larger flexbox */

flex-direction : row; /* nested items arranged horizontally */

align-items : stretch;

align-content : stretch;

justify-content : space-between;

}

header, article, nav, aside, footer {

border : thin solid #777;

}

article {

flex : 1; /* item expands to fill space within larger flexbox */

}

nav, aside {

min-width : 150px;

}

header, article, nav, aside, footer {

border-radius : 0.5em;

padding : 0.5em;

margin : 0.25em;

}

/* colors to clarify layout */

header { background-color : pink; }

article { background-color : lightgreen; }

nav { background-color : lightblue; }

aside { background-color : plum; }

footer { background-color : gold; }

As of this writing, this standardized flexbox syntax is not yet widely supported even on desktop browsers. Otherwise you can use floats to achieve the same layout.

The mobile interface is encapsulated within a @media rule, which only applies when the screen is narrow. In a desktop browser, resizing the window allows you to preview the mobile interface. The CSS replaces flexbox with conventional stacked block formatting. It also suppresses the sidebar element, and places the header and navigation elements side-by-side at the top of the screen:

@media only screen and (max-width:480px) {

section.page, section.content {

display : block; /* override flexbox */

min-height : inherit;

}

section.page {

padding : 0.5em 0.25em 0.5em 0.25em;

}

aside {

display : none; /* hide sidebar */

}

article {

min-height : 20em;

margin : 4em 0 1em 0;

}

header, nav { /* compress header & nav */

min-height : 2em;

position : absolute;

top : 0.5em;

}

header {

left : 0.5em;

width : 60%;

}

nav {

right : 0.5em;

width : 20%;

min-width : inherit;

}

}

Within each layout, you can apply more CSS to re-style elements for each interface. If re-styling them in place becomes too complex, you can instead toggle the display of alternative interface items. However, note that maintaining separate sets of markup may increase the footprint of the HTML served to mobile browsers, potentially over relatively slow or expensive data networks.

Example: High-resolution images

Along with screen size, knowing screen resolution can help improve the appearance of a mobile site. Mobile browsers operate on handsets with increasingly high-resolution retina screens. By default, these screens would render content far too small than in desktop browsers, and there is significant variation among handsets as their resolutions increase. To standardize sizing, browsers rely on an abstract grid of CSS pixels to calculate measurements. This lower-resolution grid undergoes a translation to each handset’s set of higher-resolution device screen pixels. The typical ratio of device pixels to CSS pixels ranges from 1.5 to 2 along either axis. So if your CSS specifies the same dimensions to match the image, the handset may use up to 4 pixels to represent each of the image’s pixels.

Using device-pixel-ratio media queries, you can target images to each handset so that they scale to display at the best possible resolution. The following example shows three differently sized icons set to fit as a background image within a 64-pixel-wide block:

nav:last-of-type {

width : 64px;

height : 64px;

background-image : url("img/webkit64.png");

}

@media all and (min-device-pixel-ratio:1.5) {

nav:last-of-type { background-image : url("img/webkit96.png"); }

}

@media all and (min-device-pixel-ratio:2) {

nav:last-of-type { background-image : url("img/webkit128.png"); }

}

The icon on the left below shows the distortion that occurs when viewed at the same nominal size on a browser whose device-pixel-ratio is 2. As you go to the right, you see a crisper image appropriate for the actual screen resolution:

Media Queries from JavaScript

If media queries only allowed you to assign style sheets, there would be no way to align your JavaScript with your CSS. The matchMedia interface solves that problem.

The following function specifies screen-width criteria to test whether the application is being run on browsers classified desktop tablet, touch, or unlikely low-end mobile:

function isDesign(str) {

var design;

if (window.matchMedia('only screen and (max-device-width: 320px)').matches) {

design = 'touch';

} else if (window.matchMedia('only screen and (max-device-width: 1024px)').matches) {

design = 'tablet';

} else if (window.matchMedia('screen').matches) {

design = 'desktop';

} else if (window.matchMedia('handheld').matches) {

design = 'mobile';

}

return(str == design);

}

This technique is useful, especially when deploying a hybrid site’s content over potentially low-bandwidth mobile networks. The following example changes references to high-resolution video files to lower-bandwidth variants, based on their file prefixes:

var sources = document.querySelector("video").querySelectorAll("source");

if (isDesign("touch")) {

for (i = 0, l = sources.length; i < l ; i++ ) {

sources[i].src = sources[i].src.replace(/hi_/, "lo_");

}

}

High-bandwidth content that is appropriate for desktop browsers may lead to poor performance on mobile browsers, and costly network traffic. If you deploy a hybrid site using separate interfaces for desktop and mobile browsers as described above, a sidebar element that appears in the desktop interface may be suppressed from the mobile interface:

.sidebar { display: block }

@media only screen and (max-device-width: 320px) {

.sidebar { display: none }

}

In that case, it would be inefficient to load a great deal of markup from the server that never actually displays on mobile browsers. Instead, the full markup may load conditionally, depending on which design is in effect:

<section class="sidebar"><!-- empty node --></section>

if (isDesign("desktop")) {

$(".sidebar").load("sidebar_innerHTML.html");

}

Alternately, if you want to deploy a site’s various interfaces via separate access points (such as m.website.com, touch.website.com, or website.mobi), you can use such tests to prompt mobile users who land on a desktop page if they would rather view the corresponding mobile page instead.

Media Query Listeners

Unlike the conditional tests shown above, media query listeners allow an application to dynamically respond whenever there is a change in a media query expression’s matching state.

As of this writing, there’s not yet widespread support for media query listeners among mobile browsers, and not many supported properties that might be expected to change as an application executes. Screen orientation may change, but that can also be detected with the orientationchange event. This shows both ways to implement an orientation handler:

if (!!window.matchMedia.addListener) {

window.matchMedia("(orientation:landscape)").addListener(orientationHandler);

} else {

window.addEventListener('orientationchange', function(e){

if (window.orientation == 'portrait') {

// portrait

} else {

// landscape

}

});

}

The handler is passed a MediaQueryList object, whose matches property effectively determines orientation:

function orientationHandler(mql) {

if(mql.matches) {

// landscape

} else {

// portrait

}

}

For an example of a custom landscape layout using the orientation media query, see The Mobile Viewport and Orientation.

What can you find out about a browser?

You can use media queries to test for any of the following device properties:

width, min-width, max-width, device-width, min-device-width, max-device-width: integer measurements specify pixels. The device keyword specifies the latent width of the non-resizable window used by mobile browsers, a value that doesn’t apply to resizable desktop browser windows.

height, min-height, max-height, device-height, min-device-height, max-device-height: same as above, yet vertical. Note that a mobile browser’s interface items often use some of this vertical space, so widths offer a more reliable figure.

aspect-ratio, min-aspect-ratio, max-aspect-ratio, device-aspect-ratio, min-device-aspect-ratio, max-device-aspect-ratio: accepts pairs of width/height integers, such as 3/4.

resolution, min-resolution, max-resolution: screen resolution expressed in dots per inch.

device-pixel-ratio, min-device-pixel-ratio, max-device-pixel-ratio: the number of device screen pixels that correspond to each CSS pixel, typically ranging from 1 for desktop browsers to 2 for the highest-resolution mobile screens. (On WebKit and Opera, this information is also available via window.devicePixelRatio.)

color, min-color, max-color: color depth, expressed as the number of bits used to represent each color.

color-index, min-color-index, max-color-index: number of different colors that may display at once.

orientation: either portrait or landscape.

Webkit-based browsers may also test for the presence of high-level CSS animation features: (transform-2d), (transform-3d), (transition), and (animation). (To extend functionality to earlier browser versions, specify webkit as a vendor prefix: (-webkit-transform-3d).)

Most important remaining browser features can be tested using JavaScript-based object detection. The following tests support for various HTML5-related features:

var supportsLocation = !!navigator.geolocation;

var supportsVideo = !!document.createElement("video").canPlayType;

var supportsStorage = !!window.localStorage;

When should you use media queries?

Media queries and other client-side tests enable responsive web design, allowing a single site to adapt its design to each kind of device. It’s a simple yet powerful technique that is especially appropriate for the vast number of desktop-facing websites that are not adapted for mobile, and that can benefit from a marginally better viewport-based layout. It avoids the need for separate mobile websites or compiled mobile applications. Media queries make sense in the following scenarios:

If it makes sense to deploy a set of web pages on more than one kind of device. A game that requires tilting a handset, for example, makes no sense within a desktop browser.

If the overall user interface should be perceived similarly on each device. For example, a desktop site might prompt users to access content via hierarchical categories or search queries, while a mobile site might provide a narrower range of location-specific or recently published content.

If the basic mechanism to deploy each interface matches. For example, if a desktop interface relies on conventional hyperlinks to a shifting set of web pages, while a cached mobile web application loads data dynamically via Ajax from a fixed set of files, the difference between the two approaches is more substantial than the content’s appearance on the screen.