xml

Summary

The Extensible Markup Language (XML) is a subset of SGML Its goal is to enable generic SGML to be served, received, and processed on the Web in the way that is now possible with HTML. XML has been designed for ease of implementation and for interoperability with both SGML and HTML.

Introduction

Extensible Markup Language, abbreviated XML, describes a class of data objects called XML documents and partially describes the behavior of computer programs which process them. The World Wide Web Consortium maintains the XML standard.

XML specifications

The first draft of XML was released in November 1996, the current specification (1.0 fifth edition) is consultable at the following address:

http://www.w3.org/TR/2008/REC-xml-20081126/

The goals of XML

The goals of XML, as specified by W3C, are:

- XML shall be straightforwardly usable over the Internet

- XML shall support a wide variety of applications

- XML shall be compatible with SGML

- It shall be easy to write programs which process XML documents

- The number of optional features in XML is to be kept to the absolute minimum, ideally zero

- XML documents should be human-legible and reasonably clear

- The XML design should be prepared quickly

- The XML design should be formal and concise

- XML documents shall be easy to create

- Terseness in XML markup is of minimal importance

Markup, Extensibility

Markup is all that has a special meaning, that must be well characterised: bold text, underlined text are examples of markup. An XML document is composed of markups and text: markups represent the logical structure of the document, text is the content of the document, the data. In XML all that is included between angled brackets (“<” and “>”), is considered markup, and is called tag, for example: <name> is a tag. XML is a metalanguage: Unlike HTML, which is a predefined language, it does not have predefined tags but allows the definition of new tags and new languages (there is an HTML version in XML). It is extensible. HTML is also a markup language, it was initially defined in SGML. The set of HTML rules are contained in a document (generally included in the browser) called DTD HTML (Document Type Definition). While the predefined tags of HTML are used to specify the visual aspects of the document, in XML they are used to structure the document, to define the content and to describe the data.

The components of XML

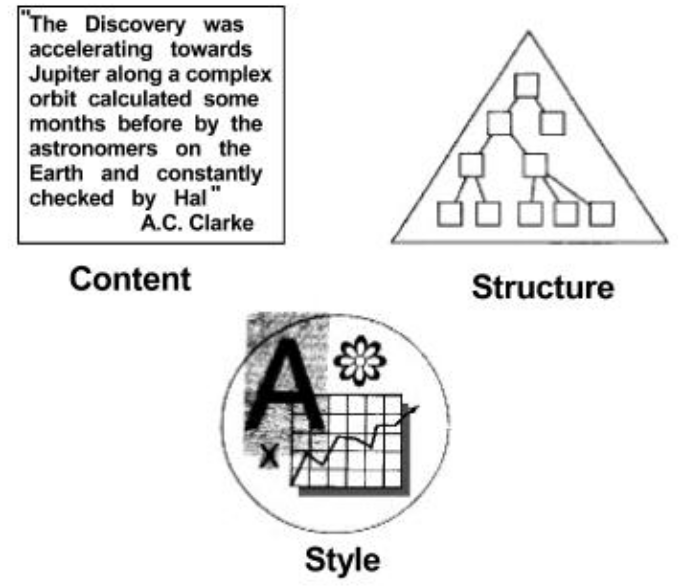

One of the most common problems today is the exchange of documents: each program stores its data in one or more proprietary formats difficult to exchange with other programs. XML has been studied to allow and facilitate data exchange between different kinds of applications, for example databases and word processors. The interest aroused by the new language is such that many software producers now intend to adopt the XML format or are already using it in theirs programmes. For a document to be easy to interpret there must be three distinct parts:

- the content;

- the specification of the elements, the structure (DTD or Schema);

- the specification of the visual aspects, the style (Stylesheet).

Why is it so important to maintain these three components distinct ?

If we have to look for information in a book, we consult the index, when this is available, otherwise we check the chapters to see whether the information contained is inherent, we then scan the paragraphs, finally we look at the content.

A particular indication such as an indentation or the use of a different character helps us to understand where a chapter or a paragraph begins: the style should help us, to understand when reading the relation of the structure with the content.

Without this distinction, an author concentrating on the visual properties risks loosing sight of the content of his/her document.

With this distinction effort can be shared: the author, who has no need to know informatics elements, can concentrate on the content of his document entrusting the visual aspect to the graphic. In addition, it is more simple to write applications that must elaborate data. Once the content is separated from the style, it is easier to integrate data from different sources and different stylesheet can be applied if needed.

If the language is modified and we want others know this or we want to use it as an exchange format, we need an open solution not a proprietary one. This means that the meaning of the extensions made must be declared, with a public DTD.

An example of an XML document

According to the design goals of XML, it should be human legible. It must be readable by any text reader, such as Unix vi or Windows Notepad and should be reasonably clear. The following example, library.xml, shows how an XML document can be written:

Figure 2 - library.xml

<?xml version=”1.0” encoding=”UTF-8”?>

<library>

<book code=”R414”>

<title>2001: A Space Odissey</title>

<author>

<first_name>Arthur Charles</first_name>

<last_name>Clarke</last_name>

</author>

<publisher>Polaris Production</publisher>

<keyword>romance</keyword >

<keyword>science-fiction</keyword >

</book>

</library>

The document begins with a prologue that contains a declaration of conformity to version 1.0 of the XML standard and to the UTF-8 encoding standard: <?xml version=”1.0” encoding=”UTF-8”?>

Elements are used to declare the associated content and are written in the form:

<element_type_name attribute_name=”attribute_value”>element content</element_type_name>

The content of an element can be of the following types: character data, parsed character data (character data that can be evaluated by parsers, programs capable of reading and interpreting XML documents), processing instructions (information to give to programs) or other nested elements. An element can have attributes, used to better specify the content. Each open tag must have a corresponding final tag; when the element is empty, like the case of BR in HTML, instead of <BR></BR> the use of the concise form <BR/> is permissible. XML is case sensitive, so a <name> tag is different from <Name> and from <NAME>. Some characters and sequences of characters are reserved and cannot be used in the names of the tags (%, xml, …). XML supports Unicode (Unicode WorldWide Character Standard), a standard code system that supports characters of the diverse languages of the world, both modern and also historical languages. With Unicode, browsers should automatically render the right character even if a document contains words written in several code sets.

DTD - Document Type Definition

The DTD contains the definition rules of tags; it denotes the elements and their order inside the XML document. Unlike SGML, its use is not compulsory, but is suggested in order to verify the validity and congruence of the document. Other than defining the elements, it defines the syntax and the relations among elements. The structure of an XML document is seen as a tree in which elements represent the nodes. The following figure (Fig. 3), represents the structure of a hypothetical library: library

Figure 1 – the three components of a document

The unique element that contains all the others is called the root element. The DTD can be internal or external to the XML document. By convention its name corresponds to that of the root element (in our example “library”). The following figure (Figure 4) shows an XML DTD, library.dtd, representing the previous defined structure:

Figure 2 - library.dtd

<!DOCTYPE library [

<!ELEMENT library (book+)>

<!ELEMENT book (title, author+, publisher, keyword+)>

<!ATTLIST book

code ID #REQUIRED>

<!ELEMENT title (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT author (first_name, last_name)>

<!ELEMENT publisher (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT keyword (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT last_name (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT first_name (#PCDATA)>

]>

A DTD can be internal or external to the XML document; generally it is written in one or more separate documents. If internal to the XML document, the DTD starts with a DOCTYPE declaration: <!DOCTYPE root_element [element, attribute, entity, notation]> otherwise this declaration must be made inside the XML document; the library.xml file would be written:

<?xml version=”1.0”?>

<!DOCTYPE library SYSTEM "library.dtd">

<library>

...

</library>

After the DOCTYPE declaration we have to declare elements:

<!ELEMENT element_name (permitted_elements_names)>

Examining the declaration of the “book” element, we can note that is composed by the elements "title", "author", “publisher” and "keyword". These elements are separated by a comma and thus must be present in that exact order in the library.xml file. Let us examine the following declaration:

<!ELEMENT person (first_name|last_name)>

<!ELEMENT person (first_name|last_name|email)*>

In the first case the “|” character means that the “person” element will be constituted by the “first_name” or by the “last_name” element; in the second case, in which a “*” character is present, by 0, 1 or more "first_name", "last_name", “email” elements in any order.

We can see that the author element is followed by the “+” character: this means that there must be one or more “author” elements.

If an element, or a group of elements listed between parentheses, is followed by the “?” character it can be present none or one times.

<!ELEMENT title (#PCDATA)> means that the title element can be composed by any character except for markup strings or special characters like ", & or ]

(PCDATA = Parsed Character Data).

Attributes are used generally as specifications of elements, to add information to elements. In this case, we can consider attributes as metadata, i.e. information about information. But attributes are also used to have a control on values; we can oblige data to be a value of a predefined list, like the enumerated type in the C language.

Attributes are declared in the form:

<!ATTRIBUTE element_name

attribute_name attribute_type default_value>

In our example, each book element will have a univocal code (ID).

Attribute types can be CDATA (character data), ID, or a list of values (enumerated type) and are declared in this way:

<!ATTLIST element_name

attribute_name attribute_type default_value>

The attribute value is compulsory when the option #REQUIRED is specified (in our example the code of the book element is compulsory), it can have no specified code if the option is #IMPLIED, or only the specified value is valid with the option #FIXED.

In addition to elements and attributes, the DTD can contain entities and notations. An XML document can be composed by elements referencing other objects; these objects are called entities. The following example shows a document internal entity:

<!ENTITY XML "eXtensible Markup Language">

In this case, during visualisation, each &XML occurrence will be replaced by the string “eXtensible Markup Language “.

Entities can be used to represent reserved characters like, for example, “<” or “>” (<, >), but can also be used to reference external objects, such as other XML documents or images, when the document does not consist of a unique file.

The following example defines an external entity:

<!ENTITY introduction SYSTEM "introduction.txt">

A document can also contain parametrical entities:

<!ENTITY % [name] "[a_list_of_names]">

for example:

<!ENTITY % headings "H1 | H2 | H3 | H4">

<!ENTITY BODY (%headings | P | DIV | BR)*>

The notation declaration is useful to identify specific types of external binary data, like for example files in “gif” format

<!NOTATION GIF87A SYSTEM “GIF”>

In case we need to preserve the space contained in an element, for example in a poem, we use the xml:space attribute set to “preserve”

<!ELEMENT poem (#PCDATA)>

<!ATTLIST poem

xml:space (default| preserve) “preserve”>

Processing instructions used to pass information to the applications are written in the form ”<?name PIdata?>” where name, called the Pitarget, is used to identify the process instruction to the programs.

The DTD is required when we have to define default attribute values, when we need to handle white spaces and when other programs need to read it to understand the structure of the document.

In order for a document to be considered “well formed”:

- it must contain at least one element;

- there must be a unique open and close tag that contains the entire document; this tag is called the root element;

- all the tags must be nested (unlike HTML <B><I>text</B></I> is not allowed);

- all the entities must be declared.

A document is said “valid” when it is associated with a DTD and respects the rules defined in the DTD.

Namespaces

An XML document may have content relative to more than one argument or discipline, or collect data from different documents or resources; this can be a source of problems because there could be several elements or attributes in the same document with the same names but relative to different contexts.

Let’s consider, for example, the word “mouse”: in one case it can be referred to a pointing device, in another to an animal or to a counter-balance or to a shy person; consider also “tree” (as a structure, or a plant).

To eliminate possible ambiguities, namespaces have been introduced. As defined by W3C, a namespace is a collection of names, identified by a URI, which are used in XML documents as element types and attribute names.

These multiple collections are also called vocabularies or markup vocabularies.

A name is constituted by two parts: the local name or the name of element type name as has been shown until now, a prefix which specifies the name of the namespace and a colon dividing the two parts. The namespace must be declared using an attribute with the prefix “xmlns” and must have a unique URI. In the following example

<html:body xmlns:html="http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40">

<html:h1>text</html:h1>

</html:body>

the body and h1 elements are mapped to the space defined by the HTML 4.0 specifications as follows:

<{http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40}body>

<{http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40}h1>text</{http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40}h1>

</{http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40}body>

Some other examples: to be added

The schema

We have described the namespaces and you will have probably noticed that they are not supported by DTDs. DTDs have other great limitations:

- they are not written in XML;

- they are not easy to write;

- they are not extensible;

- they do not specify datatypes (or, more precisely, they specify only one

type of data, the parsed character data) and very often applications need to check for specified data.

A solution has been proposed to extend the functionality of DTDs; this is known as the schema.

A schema provides an extensible way to define the XML data model: in addition to defining elements, attributes and their relationships as a DTD, it provides the possibility to add information, such as datatypes and inheritance.

Specifying datatypes makes it possible to constrain rules, such as applying ranges to values, specifying the length of a string, or the decimal precision of a number.

to be continued

Notes

draft

sections to be added