Introduction to web workers

By Eric Bidelman

Originally published July 26, 2010, updated Aug. 21, 2012

Summary

Web Workers are a means of spawning background scripts in your application, giving thread-like message passing for handling computationally intensive tasks.

The Problem: JavaScript Concurrency

There are a number of bottlenecks preventing interesting applications from being ported (say, from server-heavy implementations) to client-side JavaScript. Some of these include browser compatibility, static typing, accessibility, and performance. Fortunately, the latter is quickly becoming a thing of the past as browser vendors rapidly improve the speed of their JavaScript engines.

One thing that’s remained a hindrance for JavaScript is actually the language itself. JavaScript is a single-threaded environment, meaning multiple scripts cannot run at the same time. As an example, imagine a site that needs to handle UI events, query and process large amounts of API data, and manipulate the DOM. Pretty common, right? Unfortunately all of that can’t be done simultaneously due to limitations in browsers’ JavaScript runtimes. Script execution happens within a single thread.

Developers mimic concurrency by using techniques like setTimeout(), setInterval(), XMLHttpRequest, and event handlers. Yes, all of these features run asynchronously, but non-blocking doesn’t necessarily mean concurrency. Asynchronous events are processed after the current executing script has yielded. The good news is that HTML5 gives us something better than these hacks!

Introducing Web Workers: Bring Threading to JavaScript

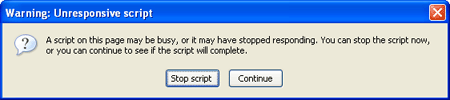

The Web Workers specification defines an API for spawning background scripts in your web application. Web Workers allow you to do things like fire up long-running scripts to handle computationally intensive tasks, but without blocking the UI or other scripts to handle user interactions. They’re going to help put and end to that nasty “unresponsive script” dialog that we’ve all come to love:

Common unresponsive script dialog

Web Workers utilize thread-like message passing to achieve parallelism. They’re perfect for keeping your UI refresh, performant, and responsive for users.

Types of Web Workers

It’s worth noting that the specification discusses two kinds of Web Workers, Dedicated Workers and Shared Workers. This article will only cover Dedicated Workers, and will refer to them as “web workers” or “workers” throughout.

Getting Started

Web Workers run in an isolated thread. As a result, the code that they execute needs to be contained in a separate file. But before we do that, the first thing to do is create a new Worker object in your main page. The constructor takes the name of the worker script:

var worker = new Worker('task.js');

If the specified file exists, the browser will spawn a new worker thread, which is downloaded asynchronously. The worker will not begin until the file has completely downloaded and executed. If the path to your worker returns an 404, the worker will fail silently.

After creating the worker, start it by calling the postMessage() method:

worker.postMessage(); // Start the worker.

Communicating with a Worker via Message Passing

Communication between a worker and its parent page is done using an event model and the postMessage() method. Depending on your browser/version, postMessage() can accept either a string or JSON object as its single argument.

Below is a example of using a string to pass “Hello World” to a worker in doWork.js. The worker simply returns the message that is passed to it.

Main script:

var worker = new Worker('doWork.js');

worker.addEventListener('message', function(e) {

console.log('Worker said: ', e.data);

}, false);

worker.postMessage('Hello World'); // Send data to our worker.

doWork.js (the worker):

self.addEventListener('message', function(e) {

self.postMessage(e.data);

}, false);

When postMessage() is called from the main page, our worker handles that message by defining an onmessage handler for the message event. The message payload (in this case “Hello World”) is accessible in Event.data. Although this particular example isn’t very exciting, it demonstrates that postMessage() is also your means for passing data back to the main thread. Convenient!

Messages passed between the main page and workers are copied, not shared. For example, in the next example the msg property of the JSON message is accessible in both locations. It appears that the object is being passed directly to the worker even though it’s running in a separate, dedicated space. In actuality, what is happening is that the object is being serialized as it’s handed to the worker and subsequently de-serialized on the other end. The page and worker do not share the same instance, so the end result is that a duplicate is created on each pass. Most browsers implement this feature by automatically JSON encoding/decoding the value on either end.

The following is a more complex example that passes messages using JSON objects.

Main script:

<button onclick="sayHI()">Say HI</button>

<button onclick="unknownCmd()">Send unknown command</button>

<button onclick="stop()">Stop worker</button>

<output id="result"></output>

<script>

function sayHI() {

worker.postMessage({'cmd': 'start', 'msg': 'Hi'});

}

function stop() {

// Calling worker.terminate() from this script would also stop the worker.

worker.postMessage({'cmd': 'stop', 'msg': 'Bye'});

}

function unknownCmd() {

worker.postMessage({'cmd': 'foobard', 'msg': '???'});

}

var worker = new Worker('doWork2.js');

worker.addEventListener('message', function(e) {

document.getElementById('result').textContent = e.data;

}, false);

</script>

doWork2.js:

self.addEventListener('message', function(e) {

var data = e.data;

switch (data.cmd) {

case 'start':

self.postMessage('WORKER STARTED: ' + data.msg);

break;

case 'stop':

self.postMessage('WORKER STOPPED: ' + data.msg + '. (buttons will no longer work)');

self.close(); // Terminates the worker.

break;

default:

self.postMessage('Unknown command: ' + data.msg);

};

}, false);

Note: There are two ways to stop a worker: by calling worker.terminate() from the main page or by calling self.close() inside of the worker itself.

Example: Run this worker here!

The Worker Environment

Worker Scope

In the context of a worker, both self and this reference the global scope for the worker. Thus, the previous example could also be written as:

addEventListener('message', function(e) {

var data = e.data;

switch (data.cmd) {

case 'start':

postMessage('WORKER STARTED: ' + data.msg);

break;

case 'stop':

...

}

}, false);

Alternatively, you could set the onmessage event handler directly (although addEventListener is always encouraged by JavaScript ninjas).

onmessage = function(e) {

var data = e.data;

...

};

Features Available to Workers

Due to their multi-threaded behavior, web workers only have access to a subset of JavaScript’s features:

- The

navigatorobject - The

locationobject (read-only) XMLHttpRequestsetTimeout()/clearTimeout()andsetInterval()/clearInterval()- The Application Cache

- Importing external scripts using the

importScripts()method - Spawning other web workers

Workers do NOT have access to:

- The DOM (it’s not thread-safe)

- The

windowobject - The

documentobject - The

parentobject

Loading External Scripts

You can load external script files or libraries into a worker with the importScripts() function. The method takes zero or more strings representing the filenames for the resources to import.

This example loads script1.js and script2.js into the worker:

worker.js:

importScripts('script1.js');

importScripts('script2.js');

This can also be written as a single import statement:

importScripts('script1.js', 'script2.js');

Subworkers

Workers have the ability to spawn child workers. This is great for further breaking up large tasks at runtime. However, subworkers come with a few caveats:

- Subworkers must be hosted within the same origin as the parent page.

- URIs within subworkers are resolved relative to their parent worker’s location (as opposed to the location of the main page).

Keep in mind that most browsers spawn separate processes for each worker. Before you go spawning a worker farm, be cautious about hogging too many of the user’s system resources. One reason for this is that messages passed between main pages and workers are copied, not shared. See Communicating with a Worker via Message Passing.

For an sample of how to spawn a subworker, see the example in the specification.

Inline Workers

What if you want to create your worker script on the fly, or create a self-contained page without having to create separate worker files? With Blob(), you can “inline” your worker in the same HTML file as your main logic by creating a URL handle to the worker code as a string:

window.URL = window.URL {{!}}{{!}} window.webkiURL;

var blob = new Blob(["onmessage = function(e) { postMessage('msg from worker'); }"]);

// Obtain a blob URL reference to our worker 'file'.

var blobURL = window.URL.createObjectURL(blob);

var worker = new Worker(blobURL);

worker.onmessage = function(e) {

// e.data == 'msg from worker'

};

worker.postMessage(); // Start the worker.

Blob URLs

The magic comes with the call to window.URL.createObjectURL(). This method creates a simple URL string which can be used to reference data stored in a DOM File or Blob object. For example:

blob:http://localhost/c745ef73-ece9-46da-8f66-ebes574789b1

Blob URLs are unique and last for the lifetime of your application (i.e., until the document is unloaded). If you’re creating many blob URLs, it’s a good idea to release references that are no longer needed. You can explicitly release a blob URL by passing it to window.URL.revokeObjectURL():

window.URL.revokeObjectURL(blobURL); // window.webkitURL.createObjectURL() in Chrome.

In Chrome, there’s a nice page to view all of the created blob URLs: chrome://blob-internals/.

Full Example

Taking this one step further, we can get clever with how the worker’s JavaScript code is inlined in our page. This technique uses a <script> tag to define the worker:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="log"></div>

<script id="worker1" type="javascript/worker">

// This script won't be parsed by JS engines because its type is javascript/worker.

self.onmessage = function(e) {

self.postMessage('msg from worker');

};

// Rest of your worker code goes here.

</script>

<script>

window.URL = window.URL {{!}}{{!}} window.webkiURL;

function log(msg) {

// Use a fragment: browser will only render/reflow once.

var fragment = document.createDocumentFragment();

fragment.appendChild(document.createTextNode(msg));

fragment.appendChild(document.createElement('br'));

document.querySelector("#log").appendChild(fragment);

}

var blob = new Blob([document.querySelector('#worker1').textContent]);

var worker = new Worker(window.URL.createObjectURL(blob));

worker.onmessage = function(e) {

log("Received: " + e.data);

}

worker.postMessage(); // Start the worker.

</script>

</body>

</html>

In my opinion, this new approach is a bit cleaner and more legible. It defines a script tag with id="worker1" and type="javascript/worker" (so the browser doesn’t parse the JavaScript). That code is extracted as a string using document.querySelector('#worker1').textContent and passed to Blob() to create the file.

Loading External Scripts

When using these techniques to inline your worker code, importScripts() will only work if you supply an absolute URI. If you attempt to pass a relative URI, the browser will complain with a security error. This is because the worker (now created from a blob URL) will be resolved with a blob: prefix, while your app will be running from a different (presumably http://) scheme. Hence, the failure will be due to cross-origin restrictions.

One way to utilize importScripts() in an inline worker is to “inject” the current URL your main script is running from by passing it to the inline worker and constructing the absolute URL manually. This will insure the external script is imported from the same origin. For example, assuming your main app is running from http://example.com/index.html (not a real site):

...

<script id="worker2" type="javascript/worker">

self.onmessage = function(e) {

var data = e.data;

if (data.url) {

var url = data.url.href;

var index = url.indexOf('index.html');

if (index != -1) {

url = url.substring(0, index);

}

importScripts(url + 'engine.js');

}

...

};

</script>

<script>

var worker = new Worker(window.URL.createObjectURL(bb.getBlob()));

worker.postMessage('''{url: document.location}''');

</script>

Handling Errors

As with any JavaScript logic, you’ll want to handle any errors that are thrown in your web workers. If an error occurs while a worker is executing, the ErrorEvent is fired. The interface contains three useful properties for figuring out what went wrong: filename - the name of the worker script that caused the error, lineno - the line number where the error occurred, and message - a meaningful description of the error. Here is an example of setting up an onerror event handler to print the properties of the error:

<output id="error" style="color: red;"></output>

<output id="result"></output>

<script>

function onError(e) {

document.getElementById('error').textContent = [

'ERROR: Line ', e.lineno, ' in ', e.filename, ': ', e.message].join('');

}

function onMsg(e) {

document.getElementById('result').textContent = e.data;

}

var worker = new Worker('workerWithError.js');

worker.addEventListener('message', onMsg, false);

worker.addEventListener('error', onError, false);

worker.postMessage(); // Start worker without a message.

</script>

Example: workerWithError.js tries to perform 1/x, where x is undefined.

Run this worker here!

workerWithError.js:

self.addEventListener('message', function(e) {

postMessage(1/x); // Intentional error.

};

A Word on Security

Restrictions with Local Access

Due to Google Chrome’s security restrictions, workers will not run locally (i.e., from file://). Instead, they fail silently! To run your app from the file:// scheme, run Chrome with the --allow-file-access-from-files flag set. NOTE: It is not recommended to run your primary browser with this flag set. It should only be used for testing purposes and not regular browsing.

Other browsers do not impose the same restriction.

Same Origin Considerations

Worker scripts must be external files with the same scheme as their calling page. Thus, you cannot load a script from a data: URL or javascript: URL, and an https: page cannot start worker scripts that begin with http: URLs.

Use Cases

So what kind of application would utilize web workers? Unfortunately, web workers are still relatively new and the majority of samples/tutorials out there involve computing prime numbers. Although that isn’t very interesting, it’s useful for understanding the concepts of web workers. Here are a few more ideas to get your brain churning:

- Prefetching and/or caching data for later use

- Code syntax highlighting or other real-time text formatting

- Spell checker

- Analyzing video or audio data

- Background I/O or polling of webservices

- Processing large arrays or humungous JSON responses

- Image filtering in <canvas>

- Updating many rows of a local web database

Demos

References

- Web Workers specification

- Using web workers from Mozilla Developer Network

- Web Workers rise up! from Dev.Opera

Attributions

Portions of this content come from HTML5Rocks! article