Position and Transformation

Summary

This article is an overview of the coordinate system, positioning and performing translations, transforms, rotation, skewing, scaling on SVG elements.

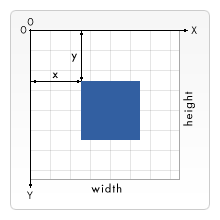

The grid

For all elements, SVG uses a coordinate system or grid system similar to the one used by canvas (and by a whole lot of other computer drawing routines). That is, the top left corner of the document is considered to be the point (0,0). Positions are then measured in pixels from the top left corner, with the positive x direction being to the right, and the positive y direction being to the bottom. Note, that this is the opposite of the way you’re taught to graph as a kid. However, this is the same way elements in HTML are positioned.

Example:

The element

<rect x="0" y="0" width="100" height="100" />

defines a rectangular from the upper left corner, that spans from there 100px to the right and to the bottom.

What are "pixels"?

In the most basic case one pixel in an SVG document maps to one pixel on the output device (a.k.a. the screen). But SVG wouldn’t have the “Scalable” in its name, if there weren’t several possibilities to change this behaviour. Much like absolute and relative font sizes in CSS SVG defines absolute units (ones with a dimensional identifier like “pt” or “cm”) and so-called user units, that lack that identifier and are plain numbers.

Without further specification, one user unit equals one screen unit. To explicitly change this behaviour, there are several possibilities in SVG. We start with the svg root element:

<svg width="100" height="100">

The above element defines a simple SVG canvas with 100x100px. One user unit equals one screen unit.

<svg width="200" height="200" '''viewBox="0 0 100 100"'''>

The whole SVG canvas here is 200px by 200px in size. However, the viewBox attribute defines the portion of that canvas to display. These 200x200 pixels display an area that starts at user unit (0,0) and spans 100x100 user units to the right and to the bottom. This effectively zooms in on the 100x100 unit area and enlarges the image to double size.

The current mapping (for a single element or the whole image) of user units to screen units is called user coordinate system. Apart from scaling the coordinate system can also be rotated, skewed and flipped. The default user coordinate system maps one user pixel to one device pixel. (However, the device may decide, what it understands as one pixel.) Lengths in the SVG file with specific dimensions, like “in” or "cm", are then calculated in a way that makes them appear 1:1 in the resulting image.

A quote from the SVG 1.1 specification illustrates this:

[…] suppose that the user agent can determine from its environment that “1px” corresponds to “0.2822222mm” (i.e., 90dpi). Then, for all processing of SVG content: […] “1cm” equals “35.43307px” (and therefore 35.43307 user units)

Transformations

Now we’re ready to start distorting our beautiful images. But first, let’s formally introduce the Template:SVGElement(“g”) element. With this helper, you can assign properties to a complete set of elements. Actually, that’s its only purpose. An example:

<g fill="red">

<rect x="0" y="0" width="10" height="10" />

<rect x="20" y="0" width="10" height="10" />

</g>

This results in two red rectangles.

All following transformations are summed up in an element’s transform attribute. Transformations can be chained simply by concatenating them, separated by whitespace.

Translation

It may be necessary to move an element around, even though you can position it with the according attributes. For this purpose, the translate() transformation stands ready.

<rect x="0" y="0" width="10" height="10" transform="translate(30,40)" />

The example will render a rectangle, translated to the point (30,40) instead of (0,0).

If the second value is not given, it is assumed to be 0.

Rotation

Rotating an element is quite a common task. Use the rotate() transformation for this:

<rect x="20" y="20" width="20" height="20" transform="rotate(45)" />

This example shows a square that is rotated by 45 degrees. The value for rotate() is given in degrees.

Skewing

To make a rhombus out of our rectangle, the skewX() and skewY() transformations are available. Each one takes an angle that determines how far the element will be skewed.

Scaling

scale() changes the size of an element. It takes two numbers, evaluated as ratio by which to scale. 0.5 shrinks by 50%. If the second number is omitted, it is assumed to be equal to the first.

Complex transformations with matrix()

All the above transformations can be expressed by a 3x3 transformation matrix. To combine several transformations, one can set the resulting matrix directly with the matrix(A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2) transformation. Detailed information about this property can be found in the SVG Recomendation.

Effects on Coordinate Systems

When using transformations you establish a new coordinate system inside the element the transformations apply to. That means, the units you specify for the element and its children might not follow the 1:1 pixel mapping, but are also distorted, skewed, translated and scaled according to the transformation.

<g transform="scale(2)">

<rect width="50" height="50" />

</g>

The resulting rectangular in the above example will be 100x100px. The more intriguing effects arise, when you rely on attributes like userSpaceOnUse and the such.

Embedding SVG in SVG

In contrast to HTML SVG allows you to embed other svg elements seamlessly. This way you can also simply create new coordinate systems by utilizing the viewBox, width and height of the inner svg element.

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.1">

<svg width="100" height="100" viewBox="0 0 50 50">

<rect width="50" height="50" />

</svg>

</svg>

The example above has basically the same effect as the one above, namely that the rect will be twice as large as specified.

Attributions

This article contains content originally from external sources, including ones licensed under the CC-BY-SA license.

Portions of this content copyright 2012 Mozilla Contributors. This article contains work licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike License v2.5 or later. The original work is available at Mozilla Developer Network: Article