Getting started with WebGL

By Erik Möller, Chris Mills

Originally published February 29, 2012

Summary

This article covers what you need to get started with WebGL

Introduction

WebGL allows you to create real 3D content and render it in a web browser. WebGL is the web implementation of OpenGL ES2 (Embedded Systems 2), and therefore allows us to run real 3D across any system with a browser that supports it and the graphics capabilities to handle such visually rich content. In web technology terms, WebGL is the 3D drawing context of the HTML5 <canvas> element.

This tutorial, created by Erik Möller in video format (with Chris Mills transcribing to create the written articles), gets you started with the basics, and forms a transcription of the material covered in Erik’s WebGL video tutorial from the beginning to time 22:25.

Note: Watch Erik’s entire WebGL video tutorial (link above) for free on YouTube. Over 2 and a half hours of WebGL tuition!

Note: Access the full WebGL 101 code example set and links to see the examples running live, at Github

Getting prepared

To get started with WebGL, and this article series, you should have:

- Some basic knowledge of JavaScript and

<canvas>. If you don’t already have this, consult such resources as dev.opera.com and MDN. - A web browser that supports WebGL. Most modern browsers support WebGL now: viable options include Opera 12.00 or higher, Chrome 9 or higher, Firefox 4 or higher, or Safari 5.1 or higher on Leopard, Snow Leopard, or Lion. You can check whether your browser supports WebGL and find updates at get.webgl.org.

- A web server that supports XHR, to serve some of the examples. Pretty much anything will do. For an easy option, you could install MAMP, or use the command

python -m SimpleHttpServer 8080on your shell/command line if you have Python installed. - A decent text editor for writing code.

Let’s get started!

Let’s begin by creating a new HTML file and saving it with a suitable name (01-minimal.html in the code download.)

First of all, enter a basic HTML5 template into it, like so, containing a simple <canvas> and a <script> element. Give your canvas an id, so we reference it via JavaScript:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<canvas id='c'></canvas>

<script>

</script>

</body>

</html>

In the script, add a line to store a reference to the canvas in a variable:

var c = document.getElementById('c');

Below, get the drawing context of this canvas, as shown below — note that we are using an experimental-webgl (3D) context here, rather than the more established 2D context:

var gl = c.getContext('experimental-webgl');

Next, we will use two WebGL-specific methods:

gl.clearColor(0,0,0.8,1);

gl.clear(gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

clearColor specifies the background colour of the canvas. We are then using clear to clear the canvas of any content, which means the background colour will then be shown. We are passing clear the COLOR_BUFFER_BIT buffer, which stores the colours of pixels drawn on the screen. (There are other buffers we could clear, such as DEPTH_BUFFER_BIT, which stores details of how far along the z axis pixels are drawn, and therefore how far into the screen they are. But we’ll not go into these in detail at this point.) Note that the clear colour we specify takes the form of four values, for red, green, blue and alpha (these all take a value of between 0 and 1, unlike in CSS colours).

If you save and run this page, it should give you a blank canvas, with a default colour of blue, like you specified above — see Figure 1.

Figure 1: A very simple WebGL output.

Note: The canvas has been created with dimensions of 300 × 150px — this is the default if you don’t specify your own width and height.

Note: WebGL code will seem rather complicated to many of you: being based on OpenGL, it is actually close to C++ code. For those of you wanting to understand it in depth, you should consult a set of C++ tutorials such as cplusplus.com/doc/tutorial.

Drawing something meaningful

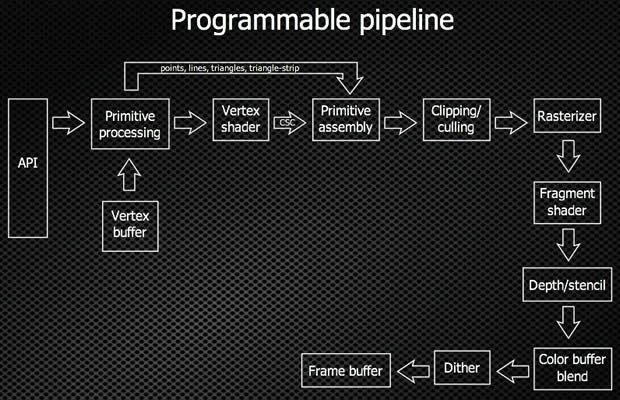

With this basic setup under our belt, let’s go forward and start by drawing an actual shape. The finished result from this section can be found as 02-minimal-draw.html in the code download. To create 3D content, WebGL uses the ES2.0 programmable pipeline, shown in Figure 2. We will refer to this multiple times throughout the walkthrough below.

Figure 2: The ES2.0 programmable pipeline (view an SVG version).

First of all, go ahead and remove the bottom two lines of script.

Next, specify a size of 400 by 400 pixels for your canvas:

<canvas id='c' width='400' height='400'></canvas>

To draw a shape, we first need to create a vertex position buffer (Vertex buffer in the programmable pipeline) to store the different vertices of the shape in. Let’s start by creating a buffer on the WebGL context, and storing it in a variable:

var vertexPosBuffer = gl.createBuffer();

Now we need to bind that buffer to the WebGL context using bindBuffer, which takes one of two possible bind points and a buffer as its arguments — the ARRAY_BUFFER of the context, and the createBuffer() object reference we defined earlier. We will also create an array to store our vertices in. Later on, we will actually upload some data to that buffer to use in drawing our shape, but we need to bind it to the context first.

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, vertexPosBuffer);

var vertices = [];

Now let’s think about the shape we want to draw — in this case we will draw a simple triangle. In such situations, it is always easier to think about what you want to draw by first sketching it out on paper, or in this case using ASCII art!

/* 2 - (0, 0.5)

/ \

/ \

(-0.5, -0.5) - 0/_____\1 - (0.5, -0.5)

*/

It is worth explaining at this point that OpenGL (and therefore, WebGL) uses a right hand coordinate system, so the x axis goes left to right, the y axis goes bottom to top, and the z axis goes out of the screen towards you. With that in mind, let’s populate the array with the coordinates we need to locate the vertices of our triangle:

var vertices = [-0.5, -0.5, 0.5, -0.5, 0, 0.5];

So here the three coordinates — (-0.5, -0.5), (0.5, -0.5) and (0, 0.5) represent points on a Cartesian plane. We are using only 2D coordinates for this example: we will move into 3D later on in the series!

As mentioned earlier, we will now upload this data into our bound buffer: we do this using bufferData(). Note how this function takes as its arguments the bind point we bound our buffer to earlier, the vertices array, which has been given a suitable data type — Float32Array — and a STATIC_DRAW label, which specifies that we want to upload the data once, and then draw it several times:

gl.bufferData(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, new Float32Array(vertices), gl.STATIC_DRAW);

Note: The TypedArray we are using here uses strict typing, unlike regular JavaScript.

To tell the program what our shape is actually going to look like, we need two more things — a vertex shader and a fragment shader (Vertex shader and Fragment shader in the programmable pipeline). These are created like so:

var vs = 'attribute vec2 pos;' +

'void main() { gl_Position = vec4(pos, 0, 1); }';

var fs = 'precision mediump float;' +

'void main() { gl_FragColor = vec4(0,0.8,0,1); }';

The vertex shader gets executed once for every vertex being passed in, passing the resulting vertex on to the primitive assembly step (Primitive assembly in the programmable pipeline: this is what creates triangles or lines out of the vertices). The primitives are then rasterised (Rasterizer in the programmable pipeline: this converts the data into pixels on the screen). Looking at the different parts of the syntax above:

attributemeans it’s per vertex — each vertex will have this data. There can be multiple attributes: you could pass in a colour per vertex as well, which would mean the vertex would have both a position and a colour in it.vec2just means it’s an (x,y) coordinate.- Shaders have to have a

main()function — here it is specifyinggl_Position(this is essential for the vertex shader — it’s the coordinate positions inside the shape we want to rasterise.) It is set to homogenous coordinates containing 4 components (hencevec4in this case) normally written as(x,y,z,w).

The fragment shader runs once for every pixel, and decides what colour each will be. In the fragment shader the one thing we have to specify in the main() function is the gl_FragColor — an RGBA colour just like the one we saw earlier, which describes the color of each pixel, a nice green in this case.

We also pass in 'precision mediump float;' to explain that we want to use medium precision for our numbers (the other two options are lowp, which is sometimes useful if you want to conserve CPU although mediump can always be handled, and highp, which is not supported in many situations, so you should steer clear of it unless you are only targeting your work at devices you know can handle it.)

Note: the pos string in the above shader code is just a variable you can set to anything you want. It will be used later on to reference the shaders.

The next couple of lines create and set the specified program as the currently active program. The createProgram() function creates and compiles the shaders before attaching them to the program and linking it. The currently active program will decide what gets drawn when you later call the drawArrays() API call.

var program = createProgram(vs,fs);

gl.useProgram(program);

Note: The createProgram() function does not yet exist: we will define it later.

Now let’s ramp it up again! We now want to get an attribute location to hook up the buffer to the program input. This is done by storing the getAttribLocation value of the shader (referenced using the pos string we specified earlier) in the vertexPosAttrib property of our program:

program.vertexPosAttrib = gl.getAttribLocation(program, 'pos');

We now add a line to specify that we want to read that buffer when we actually start drawing:

gl.enableVertexAttribArray(program.vertexPosAttrib);

Then we have to specify how the program should read the indata from the buffer, using vertexAttribPointer. Here we specify our program.vertexPosAttrib reference, the number 2 to specify that we have two values per vertex (x,y), and gl.FLOAT to specify that the data is floating point type. The two zeros at the end respectively signify that the positions are tightly packed (no gap in the data) and that we should start drawing from position zero in the buffer.

gl.vertexAttribPointer(program.vertexPosAttrib, 2, gl.FLOAT, false, 0, 0);

We have now got to the point where we have specified all the data we need to draw our triangle — woo hoo! Now we can draw the data using our program specified earlier using the following simple line:

gl.drawArrays(gl.TRIANGLES, 0, 3);

We are using drawArrays to draw our vertices out. As arguments we specify TRIANGLES because we want to draw a filled triangle (we could have used LINE_LOOP if we just wanted to draw an outline), 0 to specify that we want to start drawing from the first vertex, and the number three to declare that we have three vertices to draw.

Creating our program functions

Ah, but there’s more. To finally get our triangle displayed nicely on our canvas, we need to actually create our createProgram() function, as referenced earlier! Put the following into your script, just below the <script> tag, then we’ll dissect it line by line.

function createProgram(vstr, fstr) {

var program = gl.createProgram();

var vshader = createShader(vstr, gl.VERTEX_SHADER);

var fshader = createShader(fstr, gl.FRAGMENT_SHADER);

gl.attachShader(program, vshader);

gl.attachShader(program, fshader);

gl.linkProgram(program);

return program;

}

As you can see, this function is taking a fragment shader and a vertex shader as inputs, and creating a program variable and returning it as an output, which is then used by gl.useProgram(program);. The next two lines create the two shaders, and the two after that attach these shaders to the program we want to return. Last of all, we link the program, and return it out of the function.

An explanation of linking: Since we have two different shaders that need to work together the link step is needed to verify that they actually match up. If the vertex shader is passing data on to the fragment shader the link step makes sure the fragment shader is actually accepting that input. On some devices the actual compilation may be deferred until the link step. Akin to how it works when writing a program in C, in WebGL the shader source first gets compiled into an intermediate representation and then linked to a program. In C the source gets compiled into object files and then finally the different object files get linked into an executable.

We just have a little more work to do now — the createShader() function doesn’t yet exist, so let’s create it now. Add the following above the first function, again just below the <script> tag:

function createShader(str, type) {

var shader = gl.createShader(type);

gl.shaderSource(shader, str);

gl.compileShader(shader);

return shader;

}

This function accepts two inputs — a string and a type, and returns a shader object for us to use in our createProgram() function. In order, we create the shader object, using the specified type, specify the shader source, compile it, and then return it.

Save and run the code, and you should now have your very own green triangle, as seen in Figure 3 - woo hoo!

Figure 3: A WebGL green triangle of your very own

To get here, we used the following logical process: bear in mind that the data and program are kept separate throughout.

- The two shader sources are compiled into a program, which is passed to

useProgram()to be used. drawArrays()tells WebGL what type of primitive we want to draw using the data in the buffers.- The program will try to draw a triangle using the first three vertices from the input.

- It’ll feed each vertex in turn through the vertex shader, getting a homogenous four component coordinate for each one. It’ll then take the coordinates and rasterise a triangle, giving it spans of pixels that should be drawn to the canvas. To know what colour to draw each of the pixels in it’ll consult the fragment shader, passing it any input we’ve specified (in this case none, since we’re just drawing with a constant colour) and getting a four component colour value to put in the pixel.

Reusing common code

The above is all well and good, but in the course of our work we’ll want to create a lot more shaders and programs. Let’s make ourselves a utility library that we can reuse! Create a new JavaScript file and call it something suitable. Delete the last two functions you created out of your HTML file, and put them in your JavaScript file. It’s called webgl-utils.js in the code download.

Now reference your utility script from your HTML file, like so:

<script src='webgl-utils.js'></script>

Adding rudimentary error handling

Let’s improve these functions by adding in some error handling. To handle general JavaScript errors, we’ll use the nice window.onerror handler. First of all, add the following general error handling function to the top of your utility file:

window.onerror = function(msg, url, lineno) {

alert(url + '(' + lineno + '): ' + msg);

}

When an error is thrown, this function takes the error message, current page URL and line number the error occurred on, and outputs a hopefully readable alert message outlining all of these.

While this is useful for a rough and ready development tool, you’ll want to something cleverer in a production project, perhaps with console.log().

Now for WebGL errors. In your createShader() function, add the following construct:

if (!gl.getShaderParameter(shader, gl.COMPILE_STATUS)) {

}

Here we are using an if statement to check whether the shader has compiled successfully. If not, we will throw an error. You can throw an error message containing the current shader compile status like so:

if (!gl.getShaderParameter(shader, gl.COMPILE_STATUS)) {

throw gl.getShaderInfoLog(shader);

}

We can then do exactly the same thing for the createProgram() function, except that this time we are returning the program linking status, not the shader compilation status.

if (!gl.getProgramParameter(program, gl.LINK_STATUS)) {

throw gl.getProgramInfoLog(program);

}

so now we’ve got some error handling. Excellent!

Attributions

This content was originally published on DevOpera, Opera's Developer Network. .