High DPI Images for Variable Pixel Densities

Summary

One of the features of today’s complex device landscape is that there’s a very wide range of screen pixel densities available. Some devices feature very high resolution displays, while others straggle behind. Application developers need to support a range of pixel densities, which can be quite challenging. The goal of web app developers is to serve the best quality images as efficiently as possible. This article will cover some useful techniques for doing this today and in the near future.

Introduction

One of the features of today’s complex device landscape is that there’s a very wide range of screen pixel densities available. Some devices feature very high resolution displays, while others straggle behind. Application developers need to support a range of pixel densities, which can be quite challenging. On the mobile web, the challenges are compounded by several factors:

- Large variety of devices with different form factors.

- Constrained network bandwidth and battery life.

In terms of images, the goal of web app developers is to serve the best quality images as efficiently as possible. This article will cover some useful techniques for doing this today and in the near future.

Avoid images if possible

Before opening this can of worms, remember that the web has many powerful technologies that are largely resolution- and DPI-independent. Specifically, text, SVG and much of CSS will “just work” because of the automatic pixel scaling feature of the web (via devicePixelRatio).

That said, you can’t always avoid raster images. For example, you may be given assets that would be quite hard to replicate in pure SVG/CSS, or you are dealing with a photograph. While you could convert the image into SVG automatically, vectorizing photographs makes little sense because scaled-up versions usually don’t look good.

Background

A very short history of display density

In the early days, computer displays had a pixel density of 72 or 96dpi (dots per inch).

Displays gradually improved in pixel density, largely driven by the mobile use case, in which users generally hold their phones closer to their faces, making pixels more visible. By 2008, 150dpi phones were the new norm. The trend in increased display density continued, and today’s new phones sport 300dpi displays (branded “Retina” by Apple).

The holy grail, of course, is a display in which pixels are completely invisible. For the phone form factor, the current generation of Retina/HiDPI displays may be close to that ideal. But new classes of hardware and wearables like Project Glass will likely continue to drive increased pixel density.

In practice, low density images should look the same on new screens as they did on old ones, but compared to the crisp imagery high density users are used to seeing, the low density images look jarring and pixelated. The following is a rough simulation of how a 1x image will look on a 2x display. In contrast, the 2x image looks quite good.

Pixels on the web

When the web was designed, 99% of displays were 96dpi (or pretended to be), and few provisions were made for variation on this front. Because of a large variation in screen sizes and densities, we needed a standard way to make images look good across a variety of screen densities and dimensions.

The HTML specification recently tackled this problem by defining a reference pixel that manufacturers use to determine the size of a CSS pixel.

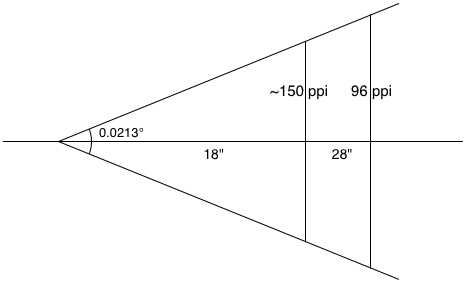

It is recommended that the reference pixel be the visual angle of one pixel on a device with a pixel density of 96dpi and a distance from the reader of an arm’s length. For a nominal arm’s length of 28 inches, the visual angle is therefore about 0.0213 degrees.

Using the reference pixel, a manufacturer can determine the size of the device’s physical pixel relative to the standard or ideal pixel. This ratio is called the device pixel ratio.

Calculating the device pixel ratio

Suppose a smart phone has a screen with a physical pixel size of 180 pixels per inch (ppi). Calculating the device pixel ratio takes three steps:

- Compare the actual distance at which the device is held to the distance for the reference pixel.Per the spec, we know that at 28 inches, the ideal is 96 pixels per inch. However, since it’s a smart phone, people hold the device closer to their faces than they hold a laptop. Let’s estimate that distance to be 18 inches.

- Multiply the distance ratio against the standard density (96ppi) to get the ideal pixel density for the given distance.idealPixelDensity = (28/18) * 96 = 150 pixels per inch (approximately)

- Take the ratio of the physical pixel density to the ideal pixel density to get the device pixel ratio.

devicePixelRatio= 180/150 = 1.2

A diagram showing one reference angular pixel, to help illustrate how devicePixelRatio is calculated.

So now when a browser needs to know how to resize an image to fit the screen according to the ideal or standard resolution, the browser refers to the device pixel ratio of 1.2 - which says, for every ideal pixel, this device has 1.2 physical pixels. The formula to go between ideal (as defined by the web spec) and physical (dots on device screen) pixels is the following:

physicalPixels = window.devicePixelRatio * idealPixels

Historically, device vendors have tended to round devicePixelRatios (DPRs). Apple’s iPhone and iPad report DPR of 1, and their Retina equivalents report 2. The CSS specification recommends that

the pixel unit refer to the whole number of device pixels that best approximates the reference pixel.

One reason why round ratios can be better is because they may lead to fewer sub-pixel artifacts.

However, the reality of the device landscape is much more varied, and Android phones often have DPRs of 1.5. The Nexus 7 tablet has a DPR of ~1.33, which was arrived at by a calculation similar to the one above. Expect to see more devices with variable DPRs in the future. Because of this, you should never assume that your clients will have integer DPRs.

Overview of HiDPI image techniques

There are many techniques for solving the problem of showing the best quality images as fast as possible, broadly falling into two categories:

- Optimizing single images, and

- Optimizing selection between multiple images.

Single image approaches: use one image, but do something clever with it. These approaches have the drawback that you will inevitably sacrifice performance, since you will be downloading HiDPI images even on older devices with lower DPI. Here are some approaches for the single image case:

- Heavily compressed HiDPI image

- Totally awesome image format

- Progressive image format

Multiple image approaches: use multiple images, but do something clever to pick which to load. These approaches have inherent overhead for the developer to create multiple versions of the same asset and then figure out a decision strategy. Here are the options:

- JavaScript

- Server side delivery

- CSS media queries

- Built-in browser features (

image-set(),<img srcset>)

Heavily compressed HiDPI image

Images already comprise a whopping 60% of bandwidth spent downloading an average website. By serving HiDPI images to all clients, we will increase this number. How much bigger will it grow?

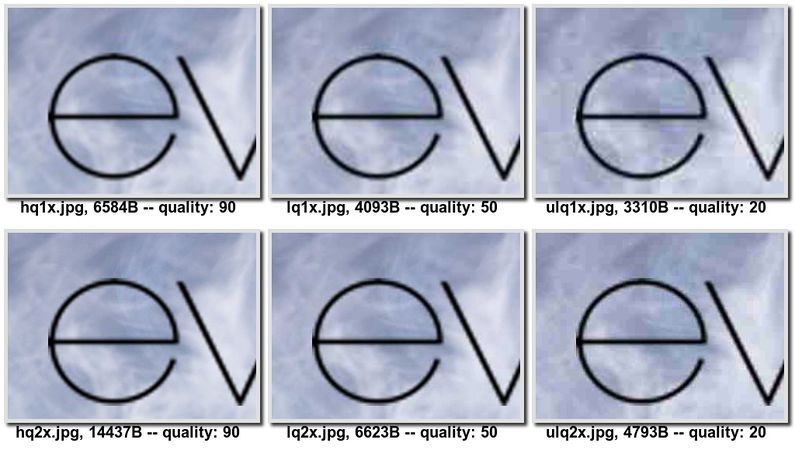

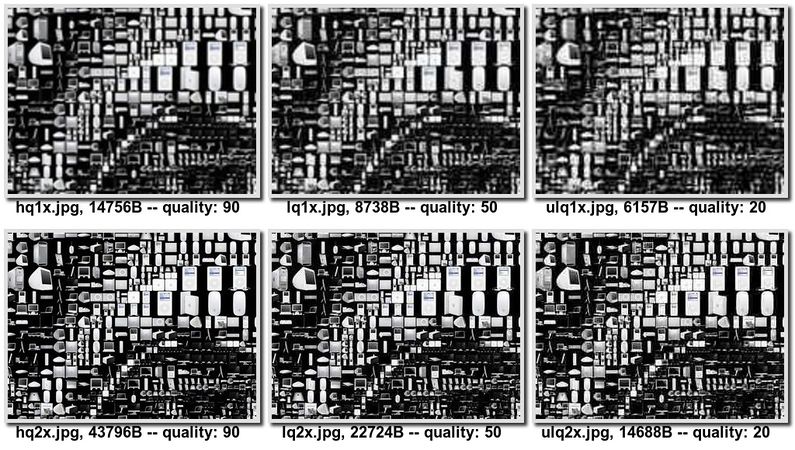

I ran some tests which generated 1x and 2x image fragments with JPEG quality at 90, 50 and 20. Here is shell script I used (employing ImageMagick) to generate them:

Samples of images at different compressions and pixel densities.

From this small, unscientific sampling, it seems that compressing large images provides a good quality-to-size tradeoff. For my eye, heavily compressed 2x imagery actually looks better than uncompressed 1x pictures.

Of course, serving low quality, highly compressed 2x imagery to 2x devices is worse than serving higher quality ones, and the above approach incurs image quality penalties. If you compare quality: 90 images to quality: 20 images, you will see a drop in crispness and increased graininess. These artifacts may not be acceptable in cases where high quality images are key (for example, a photo viewer application), or for app developers that are not willing to compromise.

The above comparison was made entirely with compressed JPEGs. It’s worth noting that there are many tradeoffs between the widely implemented image formats (JPEG, PNG, GIF), which brings us to…

Totally awesome image format

WebP is a pretty compelling image format that compresses very well while keeping high image fidelity. Of course, it’s not implemented everywhere yet!

One way is to check for WebP support is via JavaScript. You load a 1px image via data-uri, wait for either loaded or error events fired, and then verify that the size is correct. Modernizr ships with such a feature detection script, which is available via Modernizr.webp.

A better way of doing this, however, is directly in CSS using the image() function. So if you have a WebP image and JPEG fallback, you can write the following:

#pic {

background: image("foo.webp", "foo.jpg");

}

There are a few problems with this approach. Firstly, image() is not at all widely implemented. Secondly, while WebP compression blows JPEG out of the water, it’s still a relatively incremental improvement – about 30% smaller based on this WebP gallery. Thus, WebP alone isn’t enough to address the high DPI problem.

Progressive image formats

Progressive image formats like JPEG 2000, Progressive JPEG, Progressive PNG and GIF have the (somewhat debated) benefit of seeing the image come into place before it’s fully loaded. They may incur some size overhead, though there is conflicting evidence about this. Jeff Atwood claimed that progressive mode "adds about 20% to the size of PNG images, and about 10% to the size of JPEG and GIF images". However, Stoyan Stefanov claimed that for large files, progressive mode is more efficient (in most cases).

At first glance, progressive images look very promising in the context of serving the best quality images as fast as possible. The idea is that the browser can stop downloading and decoding an image once it knows that additional data won’t increase the image quality (ie. all of the fidelity improvements are sub-pixel).

While connections are easy to terminate, they are often expensive to restart. For a site with many images, the most efficient approach is to keep a single HTTP connection alive, reusing it for as long as possible. If the connection is terminated prematurely because one image has been downloaded enough, the browser then needs to create a new connection, which can be really slow in low latency environments.

One workaround to this is to use the HTTP Range request, which lets browsers specify a range of bytes to fetch. A smart browser could make a HEAD request to get at the header, process it, decide how much of the image is actually needed, and then fetch. Unfortunately HTTP Range is poorly supported in web servers, making this approach impractical.

Finally, an obvious limitation of this approach is that you don’t get to choose which image to load, only varying fidelities of the same image. As a result, this doesn’t address the "art direction" use case.

Use JavaScript to decide which image to load

The first, and most obvious approach to deciding which image to load is to use JavaScript in the client. This approach lets you find out everything about your user agent and do the right thing. You can determine device pixel ratio via window.devicePixelRatio, get screen width and height, and even potentially do some network connection sniffing via navigator.connection or issuing a fake request, like the foresight.js library does. Once you’ve collected all of this information, you can decide which image to load.

There are approximately one million JavaScript libraries that do something like the above, and unfortunately none of them are particularly outstanding.

One big drawback to this approach is that using JavaScript means that you will delay image loading until after the look-ahead parser has finished. This essentially means that images won’t even start downloading until after the pageload event fires. More on this in Jason Grigsby’s article.

Decide what image to load on the server

You can defer the decision to the server-side by writing custom request handlers for each image you serve. Such a handler would check for Retina support based on User-Agent (the only piece of information relayed to the server). Then, based on whether the server-side logic wants to serve HiDPI assets, you load the appropriate asset (named according to some known convention).

Unfortunately, the User-Agent doesn’t necessarily provide enough information to decide whether a device should receive high or low quality images. Also, it goes without saying that anything related to User-Agent is a hack and should be avoided if possible.

Use CSS media queries

Being declarative, CSS media queries let you state your intention, and let the browser do the right thing on your behalf. In addition to the most common use of media queries — matching device size — you can also match devicePixelRatio. The associated media query is device-pixel-ratio, and has associated min and max variants, as you might expect. If you want to load high DPI images and the device pixel ratio exceeds a threshold, here’s what you might do:

#my-image { background: (low.png); }

@media only screen and (min-device-pixel-ratio: 1.5) {

#my-image { background: (high.png); }

}

It gets a little more complicated with all of the vendor prefixes mixed in, especially because of insane differences in placement of “min” and “max” prefixes:

@media only screen and (min--moz-device-pixel-ratio: 1.5),

(-o-min-device-pixel-ratio: 3/2),

(-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 1.5),

(min-device-pixel-ratio: 1.5) {

#my-image {

background:url(high.png);

}

}

With this approach, you regain the benefits of look-ahead parsing, which was lost with the JS solution. You also gain the flexibility of choosing your responsive breakpoints (for example, you can have low, mid and high DPI images), which was lost with the server-side approach.

Unfortunately it’s still a little unwieldy, and leads to strange looking CSS (or requires preprocessing). Also, this approach is restricted to CSS properties, so there’s no way to set an <img src>, and your images must all be elements with a background. Finally, by relying strictly on device pixel ratio, you can end up in situations where your High-DPI smart phone ends up downloading a massive 2x image asset while on an EDGE connection. This isn’t the best user experience.

Use new browser features

There’s been a lot of recent discussion around web platform support for the high DPI image problem. Apple recently broke into the space, bringing the image-set() CSS function to WebKit. As a result, both Safari and Chrome support it. Since it’s a CSS function, image-set() doesn’t address the problem for <img> tags. Enter @srcset, which addresses this issue but (at the time of this writing) has no reference implementations (yet!). The next section goes deeper into image-set and srcset.

Browser features for high DPI support

Ultimately, the decision about which approach you take depends on your particular requirements. That said, keep in mind that all of the aforementioned approaches have drawbacks. Looking forward, however, once image-set and srcset are widely supported, they will be the appropriate solutions to this problem. For the time being, let’s talk about some best practices that can bring us as close to that ideal future as possible.

Firstly, how are these two different? Well, image-set() is a CSS function, appropriate for use as a value of the background CSS property. srcset is an attribute specific to <img> elements, with similar syntax. Both of these tags let you specify image declarations, but the srcset attribute lets you also configure which image to load based on viewport size.

Best practices for image-set

The image-set() CSS function is available prefixed as -webkit-image-set(). The syntax is quite simple, taking a one or more comma separated image declarations, which consist of a URL string or url() function followed by the associated resolution. For example:

background-image: -webkit-image-set(

url(icon1x.jpg) 1x,

url(icon2x.jpg) 2x

);

What this tells the browser is that there are two images to choose from. One of them is optimized for 1x displays, and the other for 2x displays. The browser then gets to choose which one to load, based on a variety of factors, which might even include network speed, if the browser is smart enough (not currently implemented as far as I know).

In addition to loading the correct image, the browser will also scale it accordingly. In other words, the browser assumes that 2 images are twice as large as 1x images, and so will scale the 2x image down by a factor of 2, so that the image appears to be the same size on the page.

Instead of specifying 1x, 1.5x or Nx, you can also specify a certain device pixel density in dpi.

This works well, except in browsers that don’t support the image-set property, which will show no image at all! This is clearly bad, so you must use a fallback (or series of fallbacks) to address that issue:

background-image: url(icon1x.jpg);

background-image: -webkit-image-set(

url(icon1x.jpg) 1x,

url(icon2x.jpg) 2x

);

/* This will be useful if image-set gets into the platform, unprefixed.

Also include other prefixed versions of this */

background-image: image-set(

url(icon1x.jpg) 1x,

url(icon2x.jpg) 2x

);

The above will load the appropriate asset in browsers that support image-set, and fall back to the 1x asset otherwise. The obvious caveat is that while image-set() browser support is low, most user agents will get the 1x asset.

This demo uses the image-set() to load the correct image, falling back to the 1x asset if this CSS function isn’t supported.

At this point, you may be wondering why not just polyfill (that is, build a JavaScript shim for) image-set() and call it a day? As it turns out, it’s quite difficult to implement efficient polyfills for CSS functions. (For a detailed explanation why, see this www-style discussion).

Image srcset

Here is an example of srcset:

<img alt="my awesome image"

src="banner.jpeg"

srcset="banner-HD.jpeg 2x, banner-phone.jpeg 640w, banner-phone-HD.jpeg 640w 2x">

As you can see, in addition to x declarations that image-set provides, the srcset element also takes w and h values which correspond to the size of the viewport, attempting to serve the most relevant version. The above would serve banner-phone.jpeg to devices with viewport width under 640px, banner-phone-HD.jpeg to small screen high DPI devices, banner-HD.jpeg to high DPI devices with screens greater than 640px, and banner.jpeg to everything else.

Using image-set for image elements

Because the srcset attribute on img elements is not implemented in most browsers, it may be tempting to replace your img elements with <div>s with backgrounds and use the image-set approach. This will work, with caveats. The drawback here is that the <img> tag has long-time semantic value. In practice, this is important mostly for web crawlers and accessibility reasons.

If you end up using -webkit-image-set, you might be tempted to use the background CSS property. The drawback of this approach is that you need to specify image size, which is unknown if you are using a non-1x image. Rather than doing this, you can use the content CSS property as follows:

<div id="my-content-image"

style="content: -webkit-image-set(

url(icon1x.jpg) 1x,

url(icon2x.jpg) 2x);">

</div>

This will automatically scale the image based on devicePixelRatio. See this example of the above technique in action, with an additional fallback to url() for browsers that don’t support image-set.

Polyfilling srcset

One handy feature of srcset is that it comes with a natural fallback. In the case where the srcset attribute is not implemented, all browsers know to process the src attribute. Also, since it’s just an HTML attribute, it’s possible to create polyfills with JavaScript.

This polyfill comes with unit tests to ensure that it’s as close to the specification as possible. In addition, there are checks in place that prevent the polyfill from executing any code if srcset is implemented natively.

Here is a demo of the polyfill in action.

Conclusion

There is no magic bullet for solving the problem of high DPI images.

The easiest solution is to avoid images entirely, opting for SVG and CSS instead. However, this isn’t always realistic, especially if you have high quality imagery on your site.

Approaches in JS, CSS and using the server-side all have their strengths and weaknesses. The most promising approach, however, is to leverage new browser features. Though browser support for image-set and srcset is still incomplete, there are reasonable fallbacks to use today.

To summarize, my recommendations are as follows:

- For background images, use image-set with the appropriate fallbacks for browsers that don’t support it.

- For content images, use a srcset polyfill, or fallback to using image-set (see above).

- For situations where you’re willing to sacrifice image quality, consider using heavily compressed 2x images.

Attributions

Portions of this content come from HTML5Rocks! article