Part 4: Structuring our content with HTML

Summary

Next we will dive into Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), structuring our content. This document shows an example HTML file with notes on each components that will help you learn their use.

Beginners submenu

The Beginners section covers the various aspects of web development separated in 9 parts, you can navigate through them using this list.

- 1. The beginning

- 2. A crash course in web site code

- 3. Planning

- 4. Structuring our content with HTML

- 5. Styling our content with CSS

- 6. Programming fundamentals

- 7. JavaScript

- 8. Advanced topics

- 9. Browser testing

- Glossary

Structuring Essentials

If you’re running a software, there’s plain code working behind the scenes. Similarly, with all its glitter and presentational charisma, a web page also has lots of code running (or sitting idle) behind the screen.

Every web page out there on the Internet can be seen as a document. Most web documents are written in a way so that we can distinguish images, paragraphs, titles, and so on. HTML provides a syntax that allows to make those distinctions with tags that we open and close (e.g. <strong>bold text</strong>) that we refer to as "markup". Because it gives a structure to the document.

Writing structured and re-usable HTML is an art. You have to take care of being logical (like using a header tag for a header and not your website footer!). That’s why learning to structure with best HTML practices is necessary.

In this article, we’re going to analyze the anatomy of an HTML document.

An HTML document is essentially divided into two parts: the head and the body. The head holds important metadata about the webpage, while the body holds all the content, including all text, images, colors, and the entire screen real estate. And these two parts are enclosed inside the most senior, all-encompassing html tag, that tells the browser something like “Here starts the HTML markup. Get ready.”

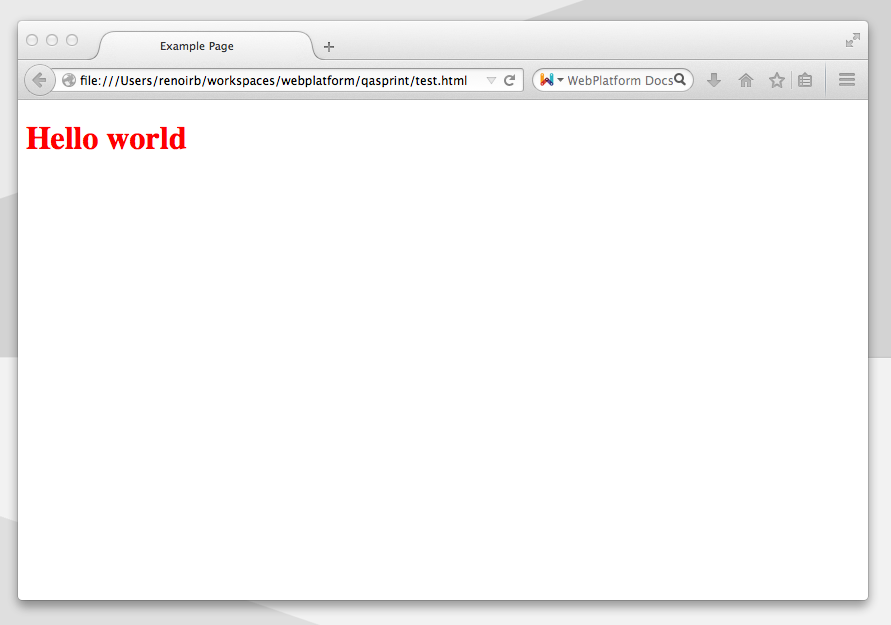

An Example Document in a Web Browser

The Code

You can copy and paste this code in a new file (e.g. index.html) and open it directly in a web browser to test it live!

You should see only a white page with a big “Hello world” written in red like the image above.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8"></meta>

<title>Example Page</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="style1.css" type="text/css"></link>

<style> h1 {

color: red;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello world</h1>

</body>

</html>

The Components Elaborated

In HTML code, a comment begins with "

<!--" and ends with "-->".<!--this is a comment-->.The

<!DOCTYPE html>comment declaration isn’t parsed in the main code. It’s used for the browser’s ease. It tells the browser what version of HTML it’s dealing with; there are others and we want to make sure that there’s no confusion. The latest HTML5 version needs only “html” for its identification, not something people had the delight of in earlier times.We open any document with the

htmltag. The "lang" part, that enables assistive devices and accessibility technologies to adapt to the language early without going through a scan, is optional but recommended.The

headincludes all the important metadata needed for the perfect display of the webpage as intended by the coder. It can include many types of declarations, but we’re using only the basic and most needed ones.- The metadata

charsetstands for character set. It defines the encoding of the webpage. UTF-8 is the universally-accepted and widest character set that includes characters of almost all popular languages of the world. If you’re writing UTF-8 encoded Korean text and the webpage is encoded in UTF-8 too, then no matter what computer opens the webpage, it will display the font typeface exactly as it should appear. Although there are other encoding methods too, but apparently there are no reasons to choose them over UTF-8 for general purposes.

- The metadata

titlepart is by far the most important piece of metadata. The text enclosed insidetitletags is the webpage’s title and is displayed on the tab, window, and page information.

- The

linktag is used to anchor together other documents or files that are needed for intended execution of the document. Here, we’re linking an CSS file (which is clear from the declarationsrel=stylesheetandtype=text/css). Thehrefattribute just tells the browser the path or location of the CSS file.

- The

- Although we’re already attaching an CSS file, but it’s also possible to include (generally document-specific) style rules within the same HTML document. A

styletag inside theheadachieves this effect. Note that it’s CSS code now, so we have to use CSS comments (and all other CSS conventions too). A CSS comment is like a programming language’s comments. /* this is a CSS comment! */

- Although we’re already attaching an CSS file, but it’s also possible to include (generally document-specific) style rules within the same HTML document. A

The

bodypart holds the main content. You’ll find ah1level heading and some text inside it.Finally, remember to close all tags! Modern browsers might face less frenzy but missing closing tags in older browsers like Internet Explorer 8 and earlier cause a havoc.

The Working

The HTML document works with the power of its tags. The tags work in sync to achieve the intended effect and structure. The CSS rules, attached either via a separate document, embedded rules within the HTML document’s head or by inline rules (not shown), add the style to the document.

The browser downloads and reads the HTML document line-by-line from top-to-bottom and renders the needed structure that makes more sense than the code. In essence, it converts code into logical user interface, though not very graphical. For example, to have a heading of largest size, we use h1.

Hopefully, you now understand the basic of HTML: structuring with various available tags. Indeed, there are many tags to explore. Most tags have additional attributes and a way of placement. From the HTML itself, you can serve different styles to different screens (two sets of styles to two separate devices like a portrait iPad and a landscape big monitor!), arrange your content with proper structure, and much, much more.

Going Over to Styles

We’ve created an CSS rule that translates as follows: “The h1 heading should have a red color.”

By default, everything is black. Here, we’re overriding the default. CSS is, frankly, all about overriding the defaults. Of course, there are more defaults already set in your browser, like the font size, positioning, heights and widths, backgrounds, borders, margins, shadows, the list goes on. That all is fully customisable in a very simple way from writing good CSS rules.

And that takes us to our next topic: Styling our content with CSS!